Learn how to get elected to the House of Representatives

Virgil leaned back in his chair, the leather creaking softly under his weight as he sipped his morning coffee. The aroma of dark roast filled the room, but the peace it promised was shattered by the familiar sound of a sharp cough. It was the conservative, clearing his throat as if preparing to address Congress itself.

“Virgil, my friend, this country is drowning in decadence because we’ve allowed money to dictate everything, including our elections,” the conservative declared, his voice gravelly yet authoritative. “This system needs discipline, not indulgence.”

Before Virgil could respond, the liberal’s voice chimed in from his left. It was softer, laced with an edge of exasperation. “Oh please, discipline? Is that what you call letting corporations run rampant while you clutch your pearls about ‘decadence’? If anything, the problem is that these campaign costs are barriers to real democracy. Regular people can’t even get a foot in the door.”

“Regular people?” scoffed the progressive, her voice tinged with righteous indignation. “The whole system is a sham! You two argue over the scraps while billionaires laugh all the way to the bank. What we need is publicly funded campaigns, full stop. Take money out of the equation entirely.”

Virgil sighed, setting his coffee down on the side table. “Can we at least ease into this debate before I’ve finished my first cup?” he muttered, knowing full well his plea would go unheard.

The conservative pressed on, unperturbed. “Look, Virgil, it’s simple. Campaigns cost money because it’s expensive to communicate with the American people. You need ads, travel, staff—that’s not free. The problem isn’t the cost; it’s who’s paying. We need transparency, not government handouts for every Tom, Dick, and Harriet who thinks they can run for office.”

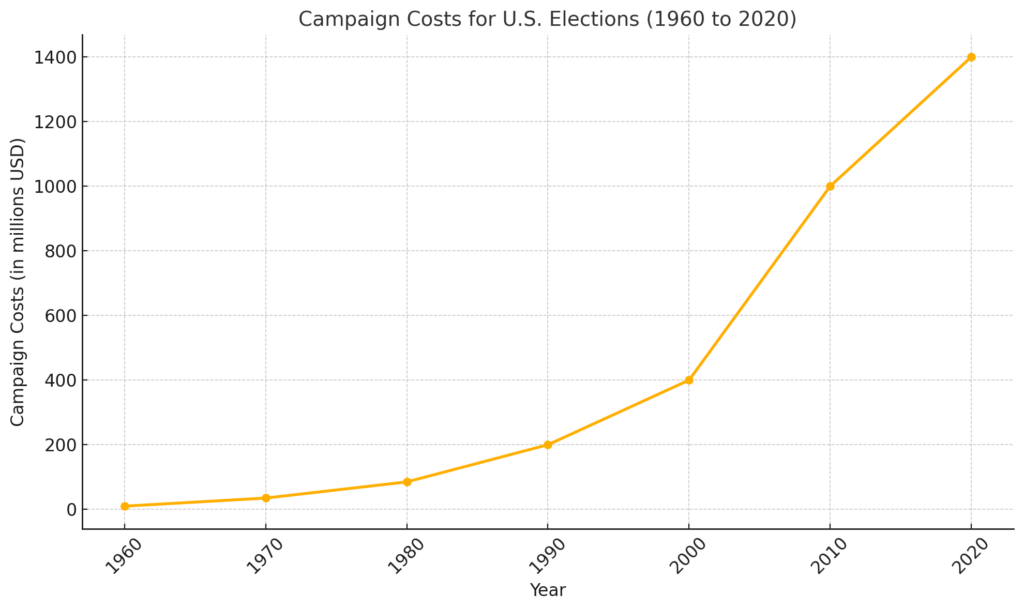

“Transparency doesn’t solve inequality,” shot back the liberal, now pacing in Virgil’s peripheral vision. “When the average House race costs $2 million, who do you think can afford that? Not teachers, not nurses, not community organizers. Only the wealthy or those beholden to the wealthy. That’s oligarchy, plain and simple.”

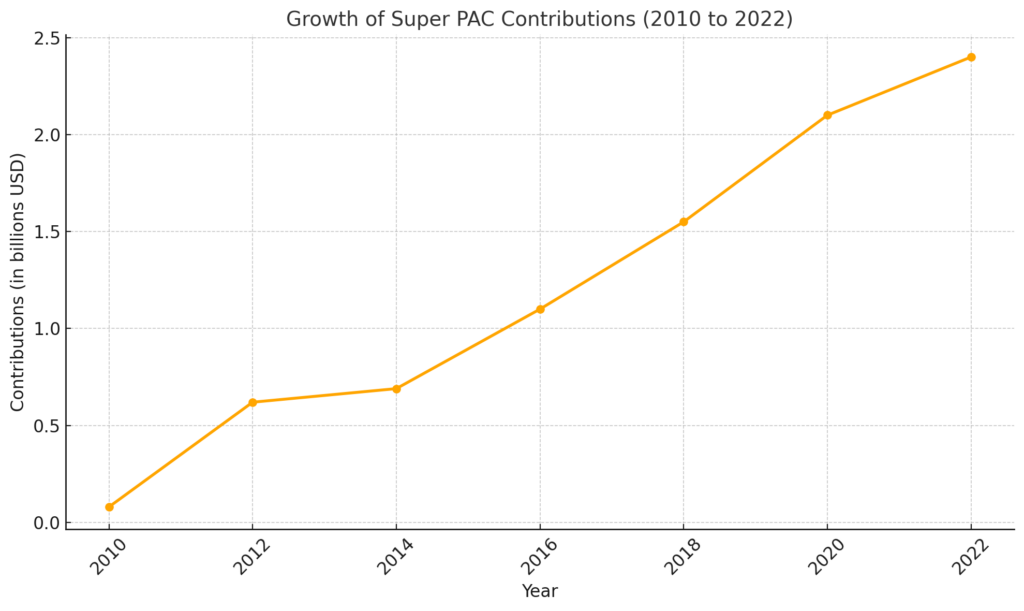

“Exactly,” the progressive interjected, pointing an unseen finger. “And that’s why the system needs to be overhauled. Get rid of Super PACs. Ban dark money. Make it illegal for corporations to donate. And yes, publicly fund campaigns so that anyone—anyone—has a fair shot.”

“Public funding?” the conservative sneered. “You want my tax dollars funding candidates I disagree with? No thank you. That’s socialism.”

“Oh, here we go with the ‘S-word’ again,” the liberal said, rolling her eyes audibly. “It’s not socialism, it’s fairness. If we don’t level the playing field, the oligarchs will continue to own every seat in Congress. And guess what? That’s not democracy.”

“And you think throwing government money at the problem will fix it?” the conservative countered. “That’ll just lead to more waste, more corruption. People will run just to collect the funds, not because they’re serious about serving.”

The progressive leaned in closer, her voice sharp and cutting. “What we have now is already corrupt! How many of these so-called ‘serious’ candidates are nothing but puppets for their donors? You’re defending a system where money equals power, and the rest of us get crumbs. It’s disgusting.”

Virgil rubbed his temples, trying to process the cacophony of arguments. “Let me get this straight,” he said, holding up a hand to silence the invisible debaters. “We agree that money has warped our democracy. But instead of finding common ground, you’re all just screaming past each other. Does that about sum it up?”

“I’m not screaming,” the conservative replied indignantly.

“Neither am I,” said the liberal and progressive in unison.

“Right,” Virgil deadpanned. “Look, the way I see it, this problem isn’t going away unless we’re willing to tackle the root causes. That means addressing both transparency and accessibility. Maybe it’s a hybrid solution: strict limits on donations, full disclosure of every dollar, and maybe some form of public funding for underrepresented candidates.”

“A compromise?” the conservative sniffed. “Typical.”

“You act like compromise is a dirty word,” the liberal shot back.

“Because it is,” the progressive muttered. “Compromise is how we’ve ended up with half-measures that fix nothing.”

Virgil stood, cutting them off with a raised hand. “You know what? Maybe you’re all part of the problem. If we’re going to fix this mess, we need less yelling and more listening. Until then, it’s just noise.”

He walked to the window, staring out at the morning sun. Behind him, the voices continued their squabble. Still, Virgil tuned them out, sipping his coffee and wondering how long it would take humanity to see what he saw: that the fight for control had blinded everyone to the need for collaboration.

Somewhere, deep in the fray of invisible voices, a faint silence began to form, like the first crack of light breaking through a storm.

Learn how to get elected to the House of Representatives conclusion

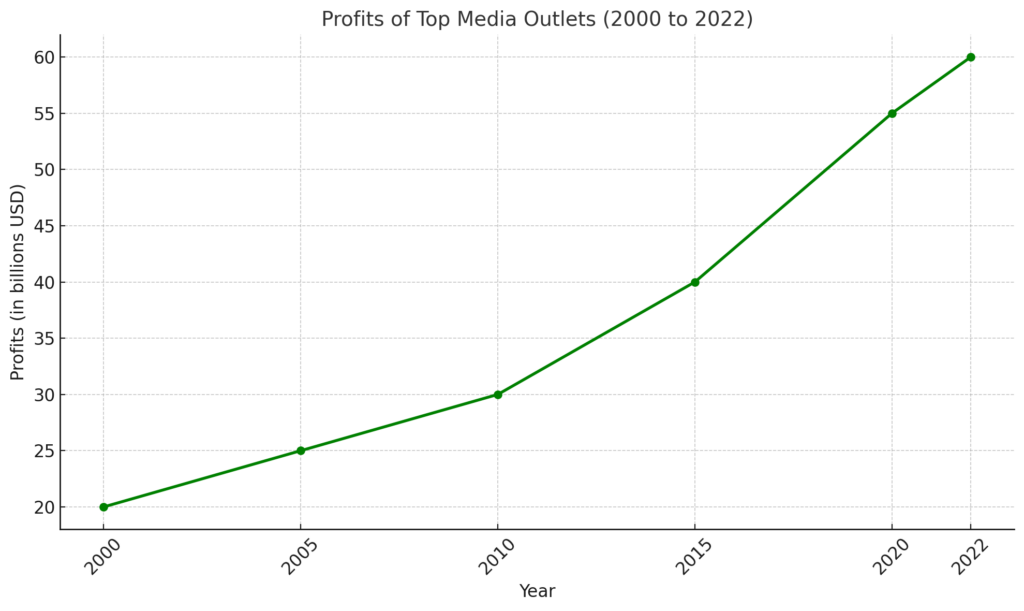

Turning back to the three, Virgil says, “It all goes back to that criminal in the 1980s. Ronald Reagan’s deregulation of the media led to the news becoming a monopoly-controlled media business that earned huge profits from advertising. Who benefits most from swing state and divisive stories? The media boards of directors. The more they can separate the people, the more they profit. Perhaps we can discuss the demise of America next time?”

Follow me on YouTube: Righter’s Doom

Follow me on Bluesky

Free novel: This Could Be It